This sort of thing?

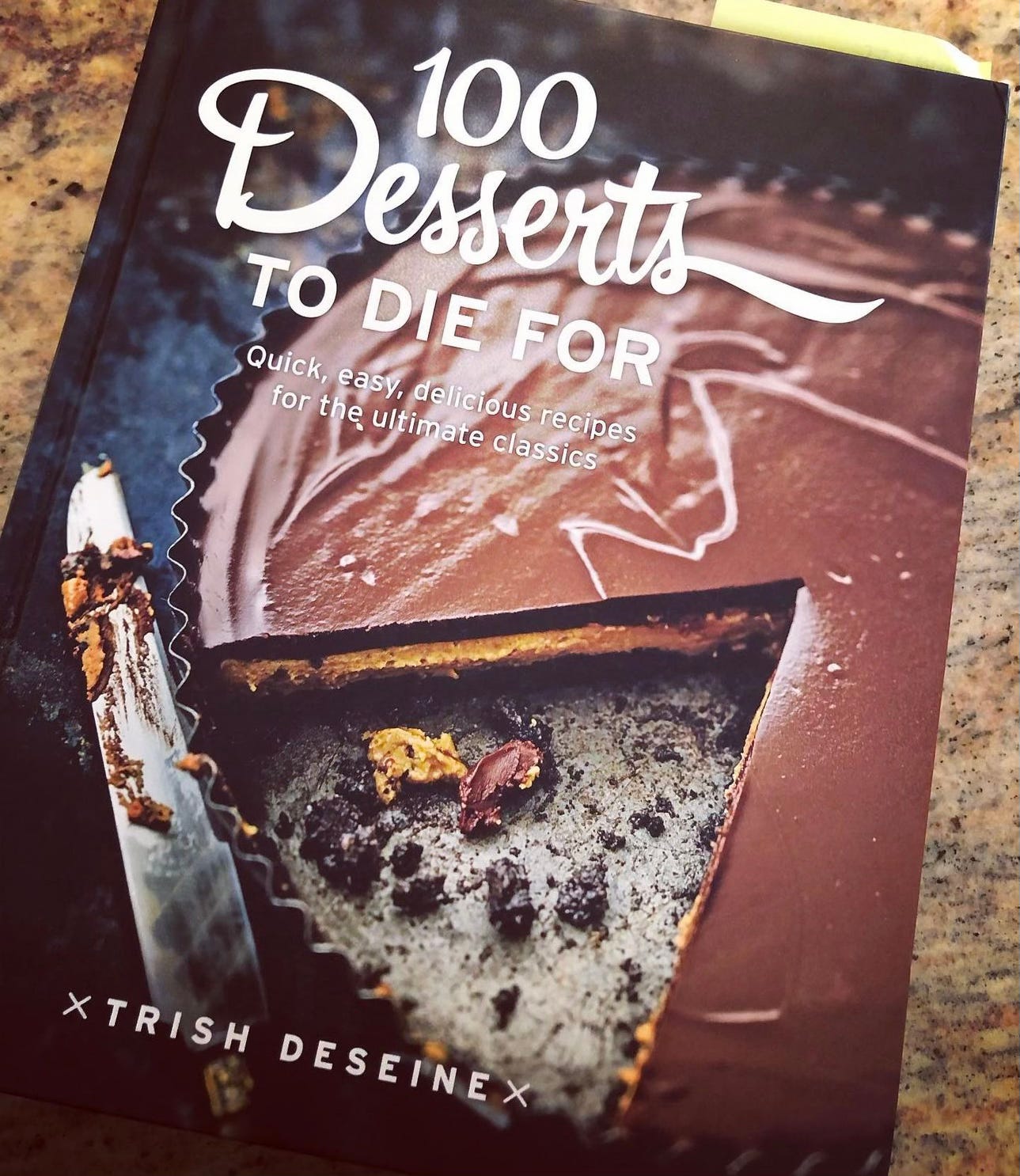

Desserts to Die For/ Et Mourir de Plaisir: Hachette Cuisine/Murdoch Books 2014

Hi everyone, and thank you so much to all my new followers, subscribers and encouragers. Here’s a first bash at the type of post I’d like to do “around” my books. They have emerged from and driven my life for twenty five years, and at the grand age of 60, I think the time is ripe to revisit them. There are recipes to come, and French house etc. chitchat.Tx

In 2013, the winter before I moved from Paris to the Languedoc, an Irish friend texted me and in a few seconds, sent me straight back to Horseshoe Farm, Co. Antrim, where I’d grown up.

I was nine. Or ten. I’m not sure. I could see myself wandering back from Sunday school just before Christmas, under flinty fast clouds, my brothers gone ahead of me, my homework done, my parents content in the kitchen, a roast beef ready in an hour or so and an afternoon’s daydreaming ahead. At the ‘Top Place’, the fields at the back of our farmyard, where often I made a detour and wrecked my Sunday shoes on the way home after Children’s Service, the land was rougher than the large stretches around the house. There were badgers’ setts, hares and rabbits, a fairy ring of forbidding black trees and, across the one lane road, a pagan betrothal stone (once someone at Bible school had whispered, « fertility stone» and made some kind of gesture with his index finger and I didn’t know what he meant or why he giggled) the Holestone, or Lovestone, set high upon a rugged, gorse-circled, stone mound, defiantly upright over the tidy Presbyterian patchwork on all sides. It always felt warm to touch, almost alive, that stone. At waist height was a perfectly round, carved hole, large enough for a girl’s hand to pass through and grasp her beloved’s on the other side.

The Holestone

“ Trish,” said my friend, “I was drinking with this mad writer guy in Killybegs. He lives in the hills above Ardara. We got talking about food and your TV show and he said you grew up in the same place. He went all misty-eyed and said he’d kissed you once in your church hall when he was sixteen. Said you dressed like a Sloane and something about not being good enough for you. »